In our deeply uneven and chaotic digital world, a offhand tweet can lead to thousands of column inches and become a global discussion point, but carefully considered work costing thousands of pounds or person hours so often appears to just disappear into the ether with barely a ripple. This, sometimes, seems very unfair.

Naturally, funders and organisational budget holders and investors and creators of strategy and campaign managers and the like want to know that they are getting a return on their investment or that a target audience is being reached or that influence is being generated. An industry of digital evaluation and monitoring has sprung up to meet this need.

The temptation has been to assume that the mechanics of the web afford much greater opportunity to measure and determine more precisely the impact of work than, say, publishing a book. And to some extent this is true. However, there is a limit, and it is reached more often than many seem to imagine.

Now, I have been a strong advocate for and a practitioner within this evaluation industry. I have created many evaluation research frameworks, trawled through analytics, designed countless questionnaires and conducted many many interviews in the name of understanding impact. I have given talks and written articles about the immense value of doing so for informing future iterations or new projects or audience understanding or for validating your work.

But perhaps I haven’t talked about enough about what you can’t measure, about the impact you never know about, and about what that means for the digital work we do.

I’ve been thinking about this for a long time, mulling over a blog post about how we need to work with a level of uncertainty around impact. So, when a couple of lovely examples dropped into my inbox recently, it seemed like the right time.

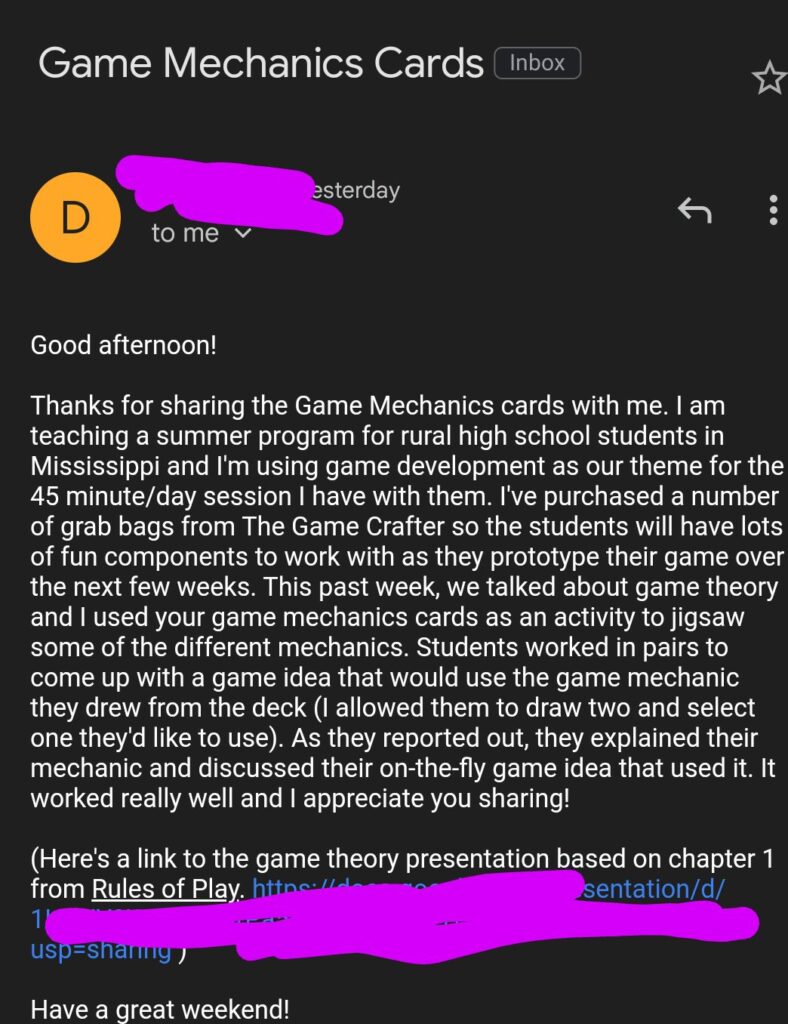

Several years ago I created a set of game mechanics cards for use in my game design workshops and posted them online for anyone to use. They are in a Google doc. It was on an unrestricted sharing link, but some years later Google changed the permissions on the document so people had to request access. It doesn’t happen very often, but now I have the opportunity to ask people requesting access how they found the cards and how they will use them. I haven’t had many responses, until I got the below email.

What a joyful thing to receive! I was so happy about this. As it happened, something similar had occurred a few weeks before, even more coincidentally. I got word of a tender that sounded up my alley from a client I’d never worked with before. When I read through the tender document I saw they had included a canvas I created for digital projects. Thrilled and rather amazed, I wrote and asked how they’d come by it. It turned out they had been pointed at it by the Lottery Heritage Fund (since I created it for a project I was mentoring for the Fund) and they told me they had found it really helpful.

Again, what a lovely ego boost and validation for having both created it and put it online. But also, what luck to even find out about either, especially the canvas. For the vast majority of things I have written, posted or created online, as a teeny weeny fish in an unimaginably gigantic pond, I am lucky if I get any comments or more than a few likes, and certainly have little information about what effect this work might have had on people. Every so often I find that something I’ve written has turned up on a syllabus or is referenced elsewhere, but for almost everything else I will never ever know if it was any use to anyone at all.

When I think about it, conversely, I have rarely had the opportunity to tell people who have created online work that has affected me deeply that I have appreciated it. Sometimes it isn’t even apparent until a long while later that it did influence me or help with something I was working on. I could be better at this, perhaps! Perhaps we all could, acknowledging and thanking our influences and inspirations.

Ultimately, though, we just have to accept that we won’t always know. Why is this important? Well, as the maxim goes “[only] what gets measured, gets managed”. It can skew the whole focus onto only making improvements that can be seen with neat numbers against them, whatever might be behind those numbers.

This ignores the fact that increased numbers, such as more eyes on your content, doesn’t tell you anything about whether those eyes belong to the people you need to see it, and what they will do with it. Or that low numbers might represent an extremely engaged audience who are about to run with your ideas and do something amazing with it. It might also ignore the longer term benefits of something in favour of short term gains that are more easily measured.

It can also be quite dispiriting for the creator who puts stuff out there and expects a clear return or response that may never appear. I know the feeling.

So my suggestion is this. Sometimes, all you (and your organisation) can do is work on what you think is right, what moves you, what you feel will be useful, and then do what you can to reach your audience. If you have any indication that the latter is happening, that may have to be enough. Imagine that if it works for you, it is very likely to work for other people like you too, and maybe years down the line you will get something lovely in your inbox to show that it still does. And, embrace uncertainty.

In yet another example of this, I started drafting this post in 2020 and came back to those notes when writing this. At the bottom, I had put a link to an article by Clare Reddington of Watershed about just this topic from January 2020. I hadn’t read it since but it was clearly a major inspiration for me thinking about this subject, and now I reread it, I see it talking about many of the same things in relation to invention and innovation https://www.watershed.co.uk/articles/invention-versus-innovation-embracing-uncertainty and “embracing uncertainty” clearly stuck in my head.

I must remember to let Clare know that her brilliant article is still inspiring me three years down the line.