[slideshare id=8093707&doc=scienceandgamesmarthahenson-110525044026-phpapp01]

Above are the slides from my talk this afternoon on games and science at the Science Communication Conference, King’s Place, London.

The aim of my talk was to demonstrate the different ways in which games can be a powerful tool for science communication and engagement. Rather than ask people to understand this in an abstract sense, I put together a varied set of game examples that have impressed and inspired me in this regard. The slides above won’t make a great deal of sense with some explanation, as it’s mostly screenshots and videos that won’t play in the browser. So, here is a bit more information about the slides, each game and why I chose it.

Overview: What games can do for you

Games can educate, they can impart information to the player. They can do more than that, though, they can really engage the player, get them to think and get them to actually use what they’ve learnt in order to successfully play they game.

They are experimental, some times almost mirroring the scientific process of forming a hypotheses and then testing it. This is true of games from Resident Evil (OK, this time, I’m going to try running past the chainsaw wielding zombie maniac to grab the shotgun shells, then hiding out here and using them from a distance to wipe him out. Let’s test it…) to Angry Birds (I reckon if I hit that wooden bit, it will topple the tower over towards me and I’ll have a clear shot at that bastard chuckling pig with a helmet sat in the middle).

They can even be used for genuine scientific research (don’t believe me? Read on…). Moreover, they are (usually) fun, a motivating factor in making people actually want to get involved. And knowing that people are having fun and doing something that is improving their knowledge and understanding has to make you feel good, right?

Games are big business, ubiquitous, demographically diverse (references from the slides)

• Well over 50% of both men and women play games online (Lightspeed Research (2009), cited by Nielsen (2009) )

Examples of games that use/educate about/research science:

Pandemic 2: Engineer an organism that destroys all humanity. Yes, the gameplay allows to modify an organism (change its resistance to drugs, symptoms etc) once it is out in the wild, which is clearly unscientific, but there is a lot in there to educate the player about disease types, transmission, factors in spread and so on. In fact, you really have to understand this to create the deadliest possible organism. PS I can never wipe out Madagascar, despite my virus killing absolutely everyone else, anyone got any tips?

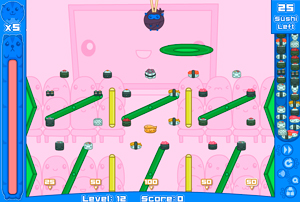

Launchball: the Science Museum has created a number of interesting games, and I understand that Launchball has been one of the most popular. It is a physics game (a popular genre, some more nice examples here), which requires you to get a ball from the start to the finish, using a combination of objects with different properties. It requires you to think about those properties and where the ball needs to go, put the objects into the space in a way you think will work, and then TEST it. It also gives you a little science factoid relevant to the level once you complete it.

Poker: The slide shows my approximately 650,000 to 1 triumph in hitting a royal flush on the river, and then utterly failing to make decent money out of it. I’ll spare you the bad beat stories, but suffice to say, when playing poker you really come to feel the probabilities. To become any sort of decent player, particularly in the more rapid online environment, you really have to understand probability and odds to the point that it becomes almost intuitive. I’m really not suggesting that everyone starts playing poker for real monies, but humans are notoriously bad at understanding risk, perhaps games that enable you to really experience it could help with that.

Routes: this was a Channel 4 game about genes, evolution and genetic testing in association with my employer, the Wellcome Trust. Not one I was personally very involved with, but one I took a great interest in because what it was attempting was pretty exciting. It was several things all at once: a documentary series on genetic testing, a series of minigames and activities, and a murder mystery in the form of an alternate reality game. Targeted at teenagers and their educators, it reached that audience and had some very positive feedback from them on the amount they learnt from playing.

High Tea: Not a science game, granted, but one with educational aims and the one I have the most information for, because I worked on it. For more information about the game see this other post I wrote, but basically it’s a strategy game that tries to give the player an insight into the Opium Wars of the Nineteenth Century. I’m including this because we have TONS of data, we did a really comprehensive evaluation on it, and because it was a massive success. We’ve had over 3 million plays to date, and the evaluation suggests it was successful in its learning objectives. Hope to publish this evaluation soon, but do contact me if you want to know more.

Foldit This is the piece de resistance, I hope. A game that was also a piece of scientific research, which has just announced that it’s made some pretty exciting findings. It was designed to test whether humans were better than computers at working out how proteins are folded with the aim of using their strategies to build better models. It looks like they’ve gone even further than that, which they claim to have proved, in solving a protein that had flummoxed scientists for 15 years in just 2 weeks and designing a whole new protein. As the blog post linked to also says, in the process they’ve also created a lot more protein experts in the world. Very impressive.

I then included a list of more examples that might be interesting, here they are with links for more info:

•

Coral Cross – an alternative reality game about flu pandemic preparedness

•

Vanished (Smithsonian and MIT) collaboration with real scientists, learning scientific techniques, collecting data etc.

Finally a cautionary tale about happens if scientists and science communicators DON’T get involved with games. The examples above are all well and good, but most games are absolutely rife with bad science (thanks to all those on twitter who helped me come up with examples of this, will add some credits later, bit rushed!). From small details such as hearing explosions in space in Halo, to more heinous errors like growing frogs who apparently have no tadpole stage in Pocket Frogs, and finally Spore. Trumpeted as a game about evolution, it ended up more about intelligent design.

So please, Science Communicators of the World, get involved with games, use them, think about them, play them and build them if you can.

Edited to add some thanks I didn’t have time to put together yesterday:

Thanks to Tomas Rawlings, firstly for giving me the opportunity to speak and secondly for talking through some ideas with me. To @PJDubyaM, @itsmapes, @paynio, @snoozeinbrief, @danthat, @docky, @steel_fox, @tracilawson, @stitchmedia and @philstuart for answering my twitter call for bad science games. And to @dannybirchall, Amy and Jen for listening to my dry run and of course thanks to SCC2011 for having me!