I used to give a talk about how museums should do more games. I would talk about how successful we’d been with this at Wellcome Collection with games like High Tea and Axon, and give other great examples from Tate, the Science Museum, the Smithsonian, and so on. However, I don’t feel that evangelising entirely makes sense any more, because the reality has proven tough.

So I have updated this talk to reflect that reality, to look into why some museums have found it actually very hard to create successful games, and to suggest a solution. Below is a video of me giving it at We Are Museums in Bucharest earlier in the year, including a short example of live game design game Cat On Yer Head in action. Since the slides from that are quite hard to make out, I’ve put them below, along with a summary.

Since the talk, I’ve left Frankly Green + Webb to go solo again, with a view to focus more on the game side of things (along with some general digital consultancy and research, and, er, yoga teaching and other bits and bobs. I do like a portfolio/random sort of career!). One of the things I offer is a game design workshop, which has proven very successful (two comments from the last one I ran: “I was really impressed by the way we managed to create our own games at the end of the session – this was really inspiring.”,”I’d say you learn a lot while having lots of fun. Great if you want to understand more about how games work and become a better commissioner of games.”).

The workshop gives you a chance to try out the principles described in the talk below, and feel confident about what it takes to create a good game. I’m looking for various outlets to run it at the moment for whoever wants to come, so more on that soon, but I have run it for specific organisations in the past, tailoring it to their needs, so if that sounds like something your museum or group would be interested in, let me know (give me a shout via twitter or linkedin). I genuinely love doing this workshop, it involves a lot of play and experimentation, and at the end of it participants have come up with some properly brilliant ideas.

On with the talk:

[slideshare id=67403766&doc=wearemuseumsmarthahenson-161019113943]

And the written version:

- Games can be a powerful medium for museums. Done well they can be engaging, educational, and reach a large audience. Look at what happened with High Tea. Over 4 million plays, amazing audience feedback/evaluation and engagement with the ideas and themes.

- But this turns out to be hard to get right, and too often goes wrong. Why?

- Lack of digital and games knowhow or dedicated resource

- Specifically a lack of understanding of the game design process from clients

- Lengthy crippling sign off processes

- A lack of flexibility in the game design process linked to funding structures – often decisions are made before games experts have had a chance to feed in and then are locked in.

- Small budgets or tight schedules that don’t allow for testing and development

- A poor fit between objectives and outcomes of the game – little learning or engagement

- Lack of understanding about the audience

- Failure to market – nobody played it

- No shared learning or insight passed on.

- This is what I’ve heard from both museum insiders and agencies/developers, some of whom have stopped doing this sort of work on commission because it’s so fruitless. And lots of cultural organisations have had budgets cut, so doing a game can seem hard to justify if they haven’t worked in the past.

- Bummer. Cat gif for light relief. But, take heart! There are so many encouraging signs. Great things are being done in board games (look at all the lovely examples in slide 11!), in indie games, in physical games. Look how popular and brilliant Now Play This was. The answer is not to stop doing games, the answer is to do the right sort of games, appropriate to your needs and resources. And the answer is to understand what best practice looks like in this area and learn from the mistakes that have been made.

- So, how do we make good games? My thoughts. There are many (many) definitions of games. But I find helpful way to understand games is to see them as a system of rules or MECHANICS that produce DYNAMICS (what you actually do in the game) that lead to AESTHETICS or the player experience overall (Robin Hunicke, Marc LeBlanc, Robert Zubek 2001 http://www.cs.northwestern.edu/~hunicke/pubs/MDA.pdf).

- As the designer, you control the mechanics, and then look at what this produces in terms of dynamics, and then how the players actually experience that.

- Too often, we think in terms of the aesthetics and the trappings of the game (the story, the art design etc), and forget that what you can control and what will make it compelling are good mechanics. And whatever learnings or objectives you have for the game, need to be embedded in the mechanics.

- (For example, we wanted players to understand that the opium trade that caused the Opium Wars was about the buying and selling of opium, in order to buy tea. So, those are the mechanics of the game – buy opium, sell opium, buy tea. You can’t play the game without picking that up.)

- So, the good news is, the process for doing this isn’t really that complicated:

- Identify your objectives (DO NOT SKIP THIS STEP)

- Identify mechanics that fit (or try, just start somewhere plausible)

- Draft a game

- Prototype and test it. Does it meet the objectives? Is it playable/fun/compelling?

- Revise based on findings from testing.

- Test again

- Revise

- Test again

- Revise

- Test again

- Revise

- etc

- What are the implications of this?

- Be clear about objectives, the mechanics will flow from that – these can be the brief

- Leave room in the development process for the actual development – must be flexible enough for this

- Test it early – leave budget and time for this

- Bring in many voices

- Think about how you are going to distribute and market it

- Evaluate and share insight – within your institution and outside too

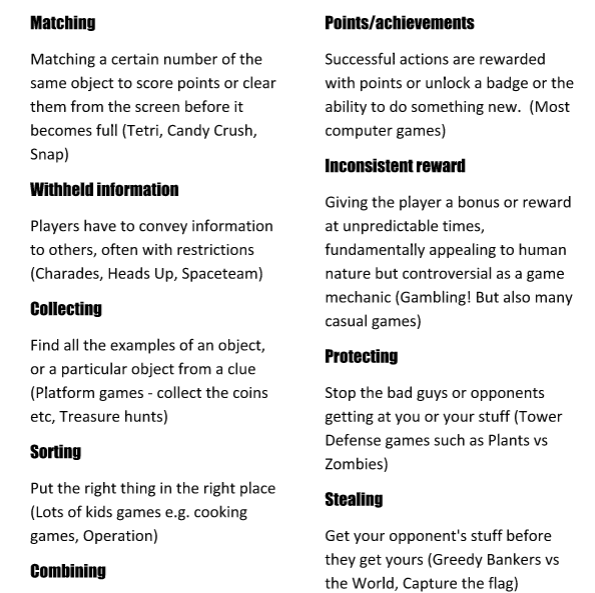

- The end. Another cat gif. PS if you want help with thinking about mechanics, why not use these game mechanics cards for inspiration? I’ve updated them a bit since, but you’ll just have to hire me for a workshop to get the latest 🙂

I’ve simplified, and generalised here, of course. Some game designers take different approaches in their work, which is fine. But this post isn’t for experienced game designers, and you can always break these rules once you’re comfortable.

I would also now add: be clear about your limitations e.g. if you don’t have sufficient budget to do a good digital game, don’t do a bad one on a small budget. Would a physical or board game work instead? (And sometimes, of course, a game isn’t the right approach at all, but you have to understand them to make a good decision about that).

I hope this is useful! Go make games 🙂